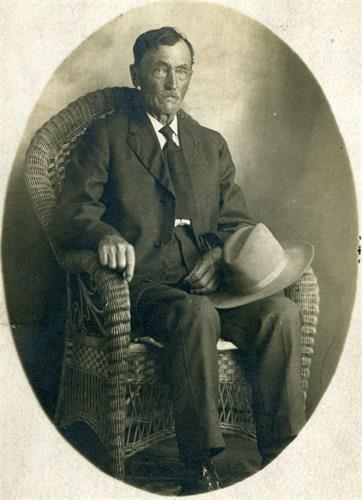

William "Braveheart" Wallace

Born: 1272 in Scotland

Died: August 23, 1305 in London, England

Married to: Marion Cornelia Bradute (1276-1297)

Children:

***Note***

When you run into a historical figure such as William Wallace, there is always a lot of legend mixed in with truth. The same can be said of any family history, I suppose, but it is important to note that it has never been confirmed that William Wallace was married or had a child. If he did not, then we are not related to him. If the legend is true, then we would be direct decendents.

Much of the legend of William Wallace was from a poem about him written by Blind Harry who claimed his book was based on information from Fr. John Blair, a childhood friend and personal chaplain of Wallace.

It is also interesting to note that on the Dyson-McCord side we are related to Robert The Bruce and in another of the Davis-Gray side of the family we are related to King Edward of England who invaded Scotland and fought William Wallace and Robert the Bruce.

*********

Scotland in the late Middle Ages established its independence from England under figures including William Wallace in the late 13th century and Robert Bruce in the 14th century. In the 15th century under the Stewart Dynasty, despite a turbulent political history, the crown gained greater political control at the expense of independent lords and restored most of its lost territory to approximately the modern borders of the country. However, the Auld Alliance with France led to the heavy defeat of a Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513 and the death of the king James IV, which would be followed by a long minority and a period of political instability.

The economy of Scotland developed slowly in this period and population of perhaps a million by the middle of the 14th century began to decline after the arrival of the Black Death, falling to perhaps half a million by the beginning of the 16th century. Different social systems and cultures developed in the lowland and highland regions of the country as Gaelic remained the most common language north of the Tay and Middle Scots dominated in the south, where it became the language of the ruling elite, government and a new national literature. There were significant changes in religion which saw mendicant friars and new devotions expand, particularly in the developing burghs. By the end of the period Scotland had adopted many of the major tenants of the European Renaissance in art, architecture and literature and produced a developed educational system. This period has been seen as seeing a clear national identity emerge in Scotland as well as significant distinctions between different regions of the country which would be particularly significant in the period of the Reformation.

The death of king Alexander III in 1286, and the subsequent death of his granddaughter and heir Margaret (called "the Maid of Norway") in 1290, left 14 rivals for succession. To prevent civil war the Scottish magnates asked Edward I of England to arbitrate, for which he extracted legal recognition that the realm of Scotland was held as a feudal dependency to the throne of England before choosing John Balliol, the man with the strongest claim, who became king as John I (30 November 1292). Robert Bruce of Annandale, the next strongest claimant, accepted this outcome with reluctance. Over the next few years Edward I used the concessions he had gained to systematically undermine both the authority of King John and the independence of Scotland. In 1295 John, on the urgings of his chief councillors, entered into an alliance with France, the beginning of the Auld Alliance.

In 1296 Edward invaded Scotland, deposing King John. The following year William Wallace and Andrew de Moray raised forces to resist the occupation and under their joint leadership an English army was defeated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. For a short time Wallace ruled Scotland in the name of John Balliol as Guardian of the realm. Edward came north in person and defeated Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk (1298). Wallace escaped but probably resigned as Guardian of Scotland. In 1305 he fell into the hands of the English, who executed him for treason despite the fact that he owed no allegiance to England.

Rivals John Comyn and Robert the Bruce, grandson of the claimant, were appointed as joint guardians in his place. On 10 February 1306, Bruce participated in the murder of Comyn, at Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries. Less than seven weeks later, on March 25, Bruce was crowned as King. However, Edward's forces overran the country after defeating Bruce's small army at the Battle of Methven. Despite the excommunication of Bruce and his followers by Pope Clement V, his support slowly strengthened; and by 1314 with the help of leading nobles such as Sir James Douglas and the Earl of Moray only the castles at Bothwell and Stirling remained under English control. Edward I had died in 1307. His heir Edward II moved an army north to break the siege of Stirling Castle and reassert control. Robert defeated that army at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, securing de facto independence. In 1320 the Declaration of Arbroath, a remonstrance to the Pope from the nobles of Scotland, helped convince Pope John XXII to overturn the earlier excommunication and nullify the various acts of submission by Scottish kings to English ones so that Scotland's sovereignty could be recognised by the major European dynasties. The Declaration has also been seen as one of the most important documents in the development of a Scottish national identity.[11]

Robert I died in 1329, leaving his 5-year-old son to reign as David and the country was ruled by a series of governors, two of whom died as a result of a renewed invasion by England four years later on the pretext of restoring Edward Balliol, son of John Balliol, to the Scottish throne, thus starting the Second War of Independence. Despite victories at Dupplin Moor (1332) and Halidon Hill (1333), in the face of tough Scottish resistance led by Sir Andrew Murray, the son of Wallace's comrade in arms, successive attempts to secure Balliol on the throne failed. Edward III lost interest in the fate of his protege after the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War with France. In 1341 David was able to return from temporary exile in France. In 1346 under the terms of the Auld Alliance, he invaded England in the interests of France, but was defeated and taken prisoner at the Battle of Neville's Cross on 17 October 1346 and would remain in England as a prisoner for eleven years. His cousin Robert Stewart ruled as guardian in his absence. Balliol finally resigned his claim to the throne to Edward in 1356, before retiring to Yorkshire, where he died in 1364. After eleven years David was released for a ransom of 100,000 marks in 1357, but he was unable to pay the ransom, resulting in secret negotiations with the English and attempts to secure the Scottish throne for an English king